Evaluation of the Spectrum Of Co-Existing Injuries In Patients With Maxillofacial Trauma: A Retrospective Study

Dr. Rajesh. P1, Dr. Vaishali. V2*

1 Professor and Head, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Chennai, India.

2 Post Graduate, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Chennai, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr. Vaishali. V, BDS,

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Chennai- 603103, India.

Tel: 8056379290, 8838017051

Email: vaish712.venkat@gmail.com

Received: December 19, 2021; Accepted: January 24, 2022; Published: January 25, 2022

Citation: Dr. Rajesh. P, Dr. Vaishali. V. Evaluation of the Spectrum Of Co-Existing Injuries In Patients With Maxillofacial Trauma: A Retrospective Study. Int J Surg Res. 2022;8(1):152-155. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2379-156X-2200033

Copyright: Dr. Vaishali. V© 2022. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the types and frequency of co-existing injuries in patients sustaining maxillofacial trauma in a tertiary care centre of Tamil Nadu.

Settings: Trauma, being referred as silent epidemic of the era, potentially results in millions of death every year worldwide.

The maxillofacial surgeon, being a part of the trauma team, gets to examine the patient first hand and thus has a shared responsibility

to thoroughly assess the injuries incurred by other systems in addition to the survey of maxillofacial injuries. This study

intends to highlight the need for an interdisciplinary management model in approaching facial trauma.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of 888 maxillofacial trauma cases reported to the emergency department during the last

five years was done. Detailed review of primary and secondary survey was done. Age, gender, mechanism of injury, type and

frequency of fracture, type and frequency of concomitant injury were recorded and subjected to statistical analysis.

Result: Associated injuries were sustained by 329 patients. Majority sustaining injuries were 20- 39 years and predominantly

males. Soft tissue injury was frequently observed. Mandibular fractures were the most common among the hard tissue injury.

Concomitant injuries observed in descending order was Neurologic, Orthopaedic, Ophthalmologic, Chest and finally abdominal.

Conclusion: Sound knowledge on the type and severity of associated injuries of other systems is mandatory for every surgeon

to keep any latent life threatening conditions at the surgeons catch.

2.Introduction

3.Case Report

4.Discussion

5.Conclusion

6.References

Keywords

Maxillofacial; Trauma; Concomitant Injuries; Traumatic Brain Injury; Oral Surgery.

Introduction

Patients with maxillofacial injuries are mostly seen to have co-existing

injuries resulting from the trauma. The extent and degree of

these injuries depend on the mechanism and impact of the trauma.

The proficiency, with which a definite assessment is made, is a

major factor in the prognosis of the patient [3]. Treatment of the

maxillofacial injuries would be complex without a comprehensive

perception of the damage incurred by other systems in the body

of the victim [1]. There is increasing recognition that patients,

who have sustained multiple injuries, benefit from early multidisciplinary

management by a specialized unit, or trauma centre [2].

It is required of the maxillofacial surgeon attending such cases in

the emergency department to promptly identify these concomitant

injuries during the primary and secondary survey to avoid

grave situations. This study intends to identify commonly occurring

collateral injuries with maxillofacial trauma to render a directed

patient care.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective analysis of a total of 6350 trauma patients, reported

to the emergency department of our institution during

the five year period, of March 2015 - March 2020, was carried

out. Of these, a detailed review of 888 patients with maxillofacial

trauma was done and data regarding age, gender, type of injury

and its frequency, mechanism of injury, concomitant injuries of

other organ systems and their frequencies was recorded. Patients

with complete medical records along with radiologic records were

included in the study. Maxillofacial injuries were recorded as soft tissue injuries, fractures of the mandible, maxilla, zygomaticomaxillary

complex, combined mandibular and middle third region

and pan facial based on the clinical and radiological medical

records. Concomitant injuries included are the neurological

including traumatic brain injury, cervical spine injury, Orthopaedic,

Ophthalmologic, Chest or pulmonologic, abdominal injuries.

Records pertaining to the concomitant injuries were either taken

from their emergency survey, or opinion obtained prior to the

treatment for maxillofacial injury or treatment record attributing

to the management of those specific system injuries. Cases with

missing or incomplete medical records were excluded from the

study. The data was tabulated and subjected to statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software version 21 was used. Chi square test was applied

and to assess the relationship between the variables Pearson’s

Correlation was used. In all the above probability value .05 is considered

as significant level.

Results

A total of 888 maxillofacial trauma patients were identified for

the study. 529(59.6 %) of them belonged to 20-39 years of age,

the maximum number to experience maxillofacial trauma followed

by 40- 60 years with a total number of 194 (21.6%), with

134 (15.1%) less than 18 years and finally above 60 years with

31(3.5%) numbers. 673 (75.8%) were males and 215 (24%) females.

There were a total of 343 hard tissue and 545 soft tissue

maxillofacial injuries present. Mandibular fractures (148) were the

most frequent, followed by zygomatico maxillary complex (77),

combined mandibular-middle third (67), isolated maxillary (37)

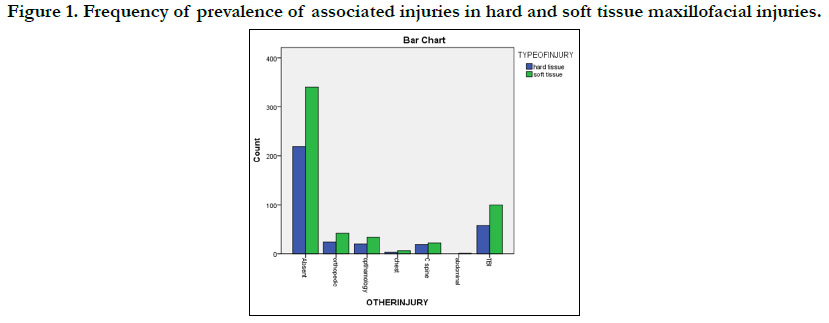

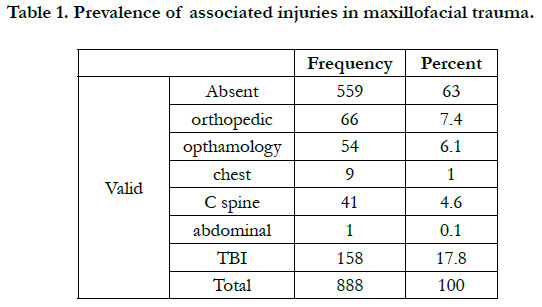

and pan facial fractures (17). Out of the 888 maxillofacial trauma

patients, 329 (37%) of them sustained associated injuries of other

systems along with maxillofacial injuries. About 17.8% of them

had traumatic brain injuries, 4.6% had cervical spine injuries, 7.4

% had orthopaedic injuries, 6.1% had ophthalmologic injuries,

1% had chest injuries and 0.1% had abdominal injuries (Table

1). Prevalence of different injuries with respect to hard and soft

tissue maxillofacial injuries has been depicted in Figure 1. No statistical

significance between the type of maxillofacial injury and

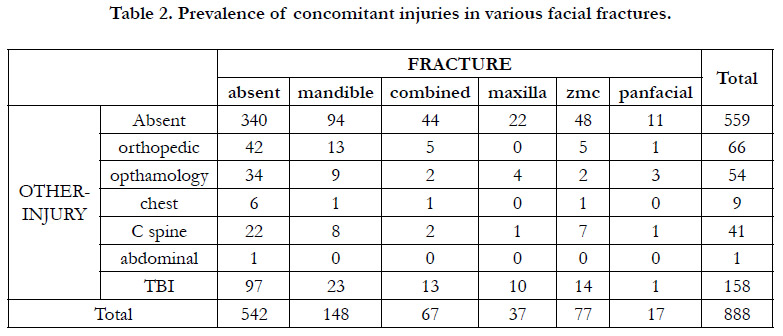

prevalence of associated injuries was found. Frequency of occurrence

of the concomitant injuries in different types of facial

fractures was analysed and depicted in Table 2. Highest number

of traumatic brain injuries were found with middle third fractures

when compared to mandibular fractures, cervical spine injuries

was highest in mandibular fractures, orthopaedic injuries in mandibular

fractures and ophthalmologic injuries in middle third fractures.

Figure 1. Frequency of prevalence of associated injuries in hard and soft tissue maxillofacial injuries.

Discussion

Nowadays, facial injuries have become a quotidian situation in the

emergency rooms as face is highly vulnerable to trauma due to

the fact that it is the most exposed region of our body [3]. It

has been reported that about 50% of head and neck collateral

injuries were observed in all trauma deaths [1]. This study aimed

at illustrating the multisystem nature of the traumatic injuries associated

with the fractures of facial skeleton. It is expected of the

high energy forces causing facial fractures to have caused injuries

to the other organ systems also. The extent and type of these

injuries however depends on the mechanism of injury, force and

its impact, patient factors like age, gender, co-existing morbidities

etc. The diagnosis of such injuries has to be done on time and a

coordinated interdisciplinary management protocol will have to

be formulated in treating a poly trauma patient. While enormous literature is available in assessing the existence of maxillofacial

fracture in poly-trauma, scarce is the information validating the

converse hypothesis. This study is designed with the aim of correlating

the other injuries existing in maxillofacial trauma since

maxillofacial surgeons form a part of the integrated trauma team

that encounters the patient first hand after the injury. Thus it is

imperative for every maxillofacial surgeon to be aware of the expected

accessory injuries that has to be addressed during the primary

and secondary survey.

In our study, the mean age group 31.40 of which 673 were males

and 215 were females. No significant statistical correlation was

found between the prevalence of concomitant injuries and, age

and gender of the study population. Road traffic accident was

the commonest cause followed by interpersonal violence and the

others. This was in accordance with the study by Deliverska et al,

Follmar et al [5], where they discussed possible random pattern

of mechanical trauma, with forces distributed to the entire body

that is conducive to injury to multiple parts of the body. With this

opinion, on correlating the existence of associated injuries to the

mechanism of trauma, Road traffic accident proves to cause poly

trauma than the assault since the latter is directed to a particular

portion of the body. . In our study most common fracture was

mandibular (16%), followed by ZMC (8.6%), combined mandibular

and middle third (7.5%), isolated maxillary (4.16%), pan facial

(1.9%), soft tissue injury (61%). Among the associated injuries,

in the descending order is the neurological including Traumatic

Head Injury and Cervical spine injury, followed by Orthopaedic,

ophthalmologic, pulmonologic and abdominal injuries.

Frequently occurring concomitant injury in our study was Traumatic

Head Injury (17.8%) which varied between mild, moderate

and severe injuries. Maxillofacial injuries comprising hard tissue as

well as soft tissue injuries can be associated with traumatic brain

injuries due to the impact of forces transmitted through the head

and neck [8]. Davidoff et al found a strong association of traumatic

head injuries with facial fractures while Haug et al reported

76% incidence of traumatic brain injuries with maxillofacial fractures.

In our study 46.7% of 124 cases of facial fractures presented

with traumatic brain injuries. Higher prevalence rate could

be related with middle face injuries owing to the complexity of

anatomy with lesser density of the bones and its proximity to the

skull. 4.6 % of the sample sustained cervical spine injuries along

with maxillofacial fractures. Hackl et al reported a rate of 19.2%

of prevalence of cervical spine injuries in their study while several

authors have reported a prevalence rate ranging between 0 to

4.3% [4]. Generally a maxillofacial trauma patient is assumed to

have sustained cervical spine injuries unless proven otherwise. If

the neurologic status of the patient with respect to injury of brain

and cervical spine could not be discretely ruled out, it is mandatory

to go for radiologic imaging prior to maxillofacial management

protocol. All the procedures should be deferred until the

patient is found neurologically stable. The pattern and severity

of these injuries highly influences the management protocol and

hence should be ruled out with utmost importance.

Neurologic injuries are succeeded by orthopaedic injuries with

7.4% of total coexisting injuries. Deliverske et al reported 22% of

orthopeadic injuries in patients with maxillofacial fractures which

supports the results of our study that had 29.7% of the total facial

fractures. This could be attributed again to multisystem involvement

of a serious trauma and its impact. Often these injuries do

not contra indicate timely management of maxillofacial injuries

and if needed, interdisciplinary simultaneous surgical management

has also been opted by the surgeons. But such decisions

purely depends on the type of procedures, duration of surgery,

general status of the patients, anticipated complications like intraoperative

blood loss or hypothermia and fitness of the patient

for anaesthetic procedures.

Ophthalmologic injuries form a significant proportion of this lot

(6.1%). These occur often as a complication of upper and middle

third fractures especially orbito- zygomatico- maxillary complex

fractures. Precise evaluation of changes in ocular structure and

function is of prime importance to alleviate the risk of morbidity

in the future. Pulmonologic injuries form of the total injuries.

Though relatively lower in number than the others stated, missed

diagnosis of the chest injuries often puts the patient’s life at risk.

Pulmonologic injuries can vary from fracture of the sternum or

rib to injury to the tissues of the lungs. Chest x-ray plays an inevitable

role in the preliminary assessment of a poly trauma patient

and if required higher imaging modality like CT or MRI can be

preferred. Often these injuries are associated with severely injured

trauma patients. Abdominal injuries are insignificant in values but

do occur in rare cases. But one should be cautious and be aware

of such occurrences so as to combat such unforeseen emergencies

if occurs.

Except for the neurological status, other injuries don’t cause significant

delay in the fractures of the facial skeleton. The results

of the study highlights the relatively high prevalence of collateral

injuries proves to be a reminder of acuity of these patients and need for a multidisciplinary approach to the trauma for rendering

directed comprehensive care in whole, volume after initial stabilization

of the patient. Precautious examination and identification

is expected of the surgeon. Most importantly, fractures from

road traffic accident should never be imagined as an isolated injury

but a part of spectrum of significant critical injury requiring

system by system assessment. Based on the results of the present

study, coexisting injuries in areas other than the face in poly

trauma patients should be expected first and foremost as trauma

that involves sufficient energy to fracture the bones of the facial

skeleton is also likely to distribute a substantial amount of force

to other parts of the body, and thus cause injury.

Conclusion

Knowledge of the frequency of concomitant injuries existing

with the maxillofacial injuries post trauma serves as guidance to

prompt identification and comprehensive management of the patient.

Also it emphasises not to narrow down the focus on maxillofacial

region but to widen the thoroughness of the assessment

to the other systems that could potentially lead to catastrophic

consequences if neglected.

References

- Scherbaum Eidt JM, De Conto F, De Bortoli MM, Engelmann JL, Rocha FD. Associated injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma at the hospital são vicente de paulo, passo fundo, Brazil. J Oral Maxillofac Res. 2013 Oct 1;4(3):e1.Pubmed PMID: 24422034.

- Down KE, Boot DA, Gorman DF. Maxillofacial and associated injuries in severely traumatized patients: implications of a regional survey. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1995 Dec;24(6):409-12.Pubmed PMID: 8636636.

- Patil SG, Munnangi A, Joshi U, Thakur N, Allurkar S, Patil BS. Associated Injuries in Maxillofacial Trauma: A Study in a Tertiary Hospital in South India. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018 Dec;17(4):410-416.Pubmed PMID: 30344378.

- Roccia F, Cassarino E, Boccaletti R, Stura G. Cervical spine fractures associated with maxillofacial trauma: an 11-year review. J Craniofac Surg . 2007 Nov 1;18(6):1259-63.

- Follmar KE, DeBruijn M, Baccarani A, Bruno AD, Mukundan S, Erdmann D, et al. Concomitant injuries in patients with panfacial fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2007 Oct 1;63(4):831-5.

- Alvi A, Doherty T, Lewen G. Facial fractures and concomitant injuries in trauma patients. Laryngoscope. 2003 Jan;113(1):102-6.

- Carlin CB, Ruff G, Mansfeld CP, Clinton MS. Facial fractures and related injuries: a ten-year retrospective analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Trauma. 1998 Summer;4(2):44-8.Pubmed PMID: 11951431.

- Rajandram RK, Syed Omar SN, Rashdi MF, Abdul Jabar MN. Maxillofacial injuries and traumatic brain injury--a pilot study. Dent Traumatol. 2014 Apr;30(2):128-32.Pubmed PMID: 23782407.

- Davidoff G, Jakubowski M, Thomas D, Alpert M. The spectrum of closedhead injuries in facial trauma victims: incidence and impact. Ann Emerg Med. 1988 Jan;17(1):6-9.Pubmed PMID: 3337417.

- Ajike SO, Adebayo ET, Amanyiewe EU, Ononiwu CN. An epidemiologic survey of maxillofacial fractures and concomitant injuries in Kaduna, Nigeria. Niger J Surg Res. 2005;7(3):251-5.

- Obuekwe ON, Etetafia M. Associated injuries in patients with maxillofacial trauma. Analysis of 312 consecutive cases due to road traffic accidents. J Med Biomed Res. 2004 Jun;3(1):30-6.

- McGoldrick DM, Fragoso-Iñiguez M, Lawrence T, McMillan K. Maxillofacial injuries in patients with major trauma. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018 Jul 1;56(6):496-500.

- Singaram M, G SV, Udhayakumar RK. Prevalence, pattern, etiology, and management of maxillofacial trauma in a developing country: a retrospective study. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 Aug;42(4):174-81. Pubmed PMID: 27595083.

- Fama F, Cicciu M, Sindoni A, Nastro-Siniscalchi E, Falzea R, Cervino G, et al. Maxillofacial and concomitant serious injuries: An eight-year single center experience. Chin J Traumatol. 2017 Feb;20(1):4-8.Pubmed PMID: 28209449.

- Pungrasmi P, Haetanurak S. Incidence and etiology of maxillofacial trauma: a retrospective analysis of King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital in the past decade. Asian Biomed. 2017 Aug 1;11(4):353-8.

- Reich W, Surov A, Eckert AW. Maxillofacial trauma - Underestimation of cervical spine injury. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016 Sep;44(9):1469-78. Pubmed PMID: 27527678.

- Choonthar MM, Raghothaman A, Prasad R, Pradeep S, Pandya K. Head injury-a maxillofacial surgeon’s perspective. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016 Jan;10(1):ZE01.