King Philip’s II of Macedonia Tomb Revisited. The Female Remains in the Antechamber are Still Unidentifiable

Delides G.S*

Professor Emeritus of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Greece.

*Corresponding Author

George S. Delides, M.D., PhD,

ProfessorEmeritus of Pathology, School of Medicine, University of Crete, Greece,

108 Magnesias str. Dionysos 14576 Athens Greece.

Tel: +306944985504

Email: delides@otenet.gr

Received: November 11, 2019; Accepted: November 20, 2019; Published: November 21, 2019

Citation: Delides G.S. King Philip’s II of Macedonia Tomb Revisited. The Female Remains in the Antechamber are Still Unidentifiable. Int J Forensic Sci Pathol. 2019;6(3):411-416. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2332-287X-1900086

Copyright: Delides G.S© 2019. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

The golden chests bearing the emblem of the Macedonian Royal family contained in two marble sarcophagi found in 1977 in the main chamber and antechamber of the unlooted Royal Tomb II at Aegae, Greece, contained the remains of two individuals, a man and a woman.

The man in the main chamber has been identified as King Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great.

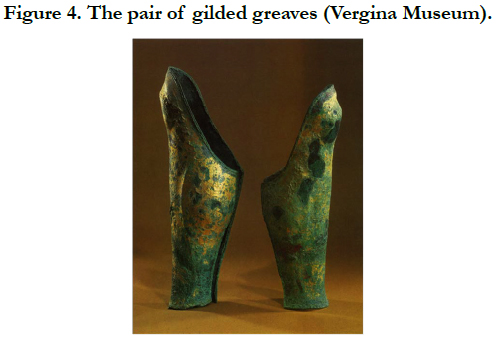

A pair of unequal gilded greaves, the left one shorter by 2.6 cm and narrower by 3.5 cm compared to the right one, an indication of the lameness of their owner, was found in the antechamber. There is not enough evidence that they belong to the woman buried and the possibility they are part of the ceremonial armor found in the main chamber cannot be excluded.

The woman’s age remains disputed, following criticism of the method used in estimating it. Whether she is King Philip’s seventh wife/concubine, daughter of Scythian king Atheas, or Cleopatra, King Philip’s wife, remains still open to discussion and any uncertainties need to be further explored.

2.Introduction

3.The Tombs

3.1 Tomb I

3.2 Tomb II

3.3 Findings in the Main Chamber

3.4 Findings in the Antechamber

3.5 Tomb III

3.6 Tomb II Occupants

3.7 Philip’s Leg Wound

3.8 The Greaves and their Owner

3.9 The woman in the Antechamber

4.Discussion

4.1 A Forensic Analysis

5.Conclusion

6.Acknowledgment

7.References

Keywords

Philip’s II Tomb; Woman in Antechamber; Vergina; Macedonia.

Introduction

In 1977, Manolis Andronikos, Professor of Archaeology at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, unearthed three royal tombs at the Great Tumulus of Aegae (Vergina), the ancient capital of the kingdom of Macedonia, Greece. His findings are presented in his book of 1984 “Vergina, The Royal Tombs” [1].

It was found looted. Its interior wall was superbly painted, depicting the abduction of Persephone by Pluto. It contained the inhumed but not cremated remains of a man, a woman and a neonate.

It was found unlooted and intact. There were a main chamber and an antechamber.

A marble sarcophagus containing a gold chest (larnax) with an embossed starburst, the emblem of the Macedonian royal family was found. Inside the chest, were the cremated remains of a middle- aged man and a golden wreath. Parts of a ceremonial suit of armors, an iron cuirass with gold decoration, a ceremonial shield with decorations of gold and ivory and an iron helmet, along with several other luxury items were found in the main chamber. Three pairs of common bronze greaves were also found.

The man’s bones were examined and age-determined [2]. Degenerative bone changes were indicative of a middle age man with riding markers existing on the iliac crest. Six Schmorl’s nodes were seen in the lower thoracic vertebrae [3].

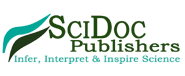

Another marble sarcophagus containing asmaller gold chest (larnax) bearing the starburst of the Macedonian royal family was found. Inside the larnax werethe cremated remains of a woman wrapped in an embroidered cloth and a gold diadem (Figure 1). Next to sarcophagus was a gold wreath of myrtle leaves and flowers, a unique piece of Greek art.

Nearby the door connecting the antechamber and main chamber a gold cover of a “gorytos” (combined bow-and arrow case) and a pair of gilded greaves of different size was found (Figures 2,3,4). The gorytos was of Scythian art similar to those discovered in tombs in southern Russia [1]. Arrowheads were inside the gorytos. Three iron spearheads were also found in the antechamber.

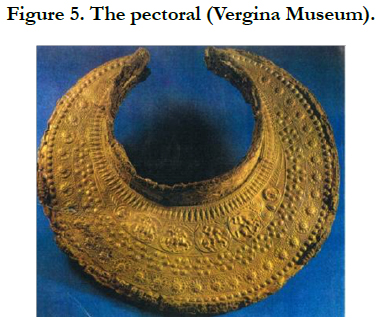

A gilded, unique in luxury, pectoral (neckband) probably made for a Thracian ruler [1], similar to those found in Thracian tombs in Bulgaria, was also discovered in the antechamber (Figure 5). These neckbands formed a complement to a cuirass protecting the neck and chest of the warrior. A cuirass or remnants of it were not found in the antechamber.

Several items including a pair of gilded greaves, which would indicate a royal burial, were also found in Tomb III. The burnt bones of a young man between thirteen and sixteen years of age were within a silver urn; they are believed to belong to Alexander IV, son of Alexander the Great and Roxane, executed by Cassander in 310 BC [4].

The only two Macedonian kings likely to have been buried in the royal tombs at Aegae (Vergina) were Philip II, Alexander’s father and Philip III Arrhidaios, Alexander’s paternal half-brother. Their respective wives, Cleopatra and Eurydice, were supposed to have been buried with them.

M. Andronikos, based his identification as that of Philip II in the main chamber of Tomb II, on a number of historical and archaeological facts detailed in his book [1]. He excluded Arrhidaios and Eurydice as being the occupants of Tomb II.

A survey of previous discussions on Tomb II, its occupants and the items found in there, was presented by M. Hatzopoulos [5]. A long list of scholars who shared Andronikos’ positions challenging those attributing the Tomb II to Arrhidaios, is sited. According to J. Lane Fox “This article is the celestial starting point for everyone who takes up these subjects and their bibliography” J. Lane Fox criticizes the main arguments in favor of Arrhidaios and further states: “I conclude with further observations on why the Tomb II, is certainly not Philip III (Arrhidaios). That red herring can now be discarded from historical scholarship” [6].

In 2015 Bartsiokas et al., examined the bones found in Tomb I and revealed a hole (likely produced by a penetrating weapon, e.g. a lance) below the level of the femoral condyles in the left knee. He concluded that the findings were consistent with the historically documented Philip’s lameness, and that “Philip II, his wife Cleopatra and their newborn child are the occupants of Tomb I, over turning the current opinion of the archaeological establishment that TombII belongs to Philip II. As a consequence, Tomb II could only belong to King Arrhidaios and Eurydice and may well contain some of the armor of Alexander the Great” [7].

In a previous paper [8], the author (GSD) has criticized Bartsiokas’ conclusions as inconsistent with the pathological findings described and the historical data regarding Philip’s lameness.

In 339 BC Philip II was severely wounded by a lance that penetrated his leg during a battle fought against the Thracian tribe of Triballoi. He recovered and in August 338 he fought against the Athenians at the battle of Chaeroneia. Nevertheless, from then on, the wound left him lame.

The site of Philip’s wound is not definitely recorded in historical data. Demosthenes, being Philip’s contemporary, mentions “the leg”, Seneca “the lower leg”, whereas both Justin and Plutarch mention “the femur” [9].

Didymus, who lived in the first century AD, records a wound in the right femur from a Macedonian “sarissa” being the only one that points to Philip’s right thigh [10]. It is not clear from which author Didymus draws his information. It is probable that he refers to Marsyas of Macedon from Pella, Philip’s contemporary. Marsyas is the author of “Makedonika” a history of Macedonia in 10 books, starting from earlier times up to 331 BC. Only fragments of “Makedonika” have survived [11].

Justin further mentions that the spear went through Philip’s thigh and killed his horse [9]. Didymus sources commented that the weapon was a “sarissa”, a Macedonian lance and specified the “right thigh”. According to Gabriel, Didymus likely means the Scythian long cavalry lance and not the Macedonian infantry sarissa [12]. The specification of the weapon as “sarissa” led Foucart to propose Philip might have been wounded by one of his own men [13].

In fact, as Riginos has commented, there was much doubt in antiquity concerning which leg was wounded; therefore, the question “in which leg was Philipp lame” could not easily be answered [9].

Andronikos, commenting on the greaves, assumes the left leg to be the one wounded; Bartsiokas [7] also disregards Didymus report and points to the left leg being wounded, in order to support his findings of Tomb I.

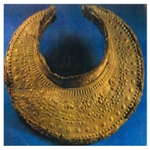

One might infer, from a forensic point of view, which was Philip’s wounded leg, based upon Justin’s description. As Gabriel notes, for “Philip’s horse to have been instantly killed by the same lance that struck Philip in the leg, the horse’s heart must have been pierced through [12]. The horse’s heart is located in the thorax between the lungs, 60% lying to the left of the media plane (Figure 6). Taking into account the rider’s position, it is plausible the lance penetrated Philip’s left leg and pierced the horse’s heart (Figure7).

A pair of gilded greaves of unequal length was found in the antechamber of Tomb II, next to the gorytos. The left was shorter by 3.5 cm in length and narrower by 0.7 cm in diameter (height: right 41.5 cm, left 38 cm; diameters: right 9.7 cm, left 9cm) [1].

Antikas and Wynn-Antikas remeasured the antechamber’s unequal greaves. The height of the right greave is set at 41.6 cm and its maximum diameter 33.5 cm(!) [3]. The reported height of the left greave is not consistent by the one sited by Andronikos in his book [1]. It appears there is a discrepancy between the two measurements by 1 cm (39 cm and 38 cm). Undoubtedly, the two diameters sited by Antikas (30 cm and 33.5 cm) are erroneous.

Taking into account the documented Philip’s II lameness, Andronikos had reservations to utilize the difference in the greaves’ length as a tool for identifying Philip’ II as the dead individual in Tomb II.

He considers two possible interpretations: “a) that the difference is really to be ascribed to Philip’s lameness. Being obliged to move and to bend each leg differently, one greave had to be shorter so that it did not impede the bending of the knee; the disparity therefore is not due to a difference in the size of the tibia but was to ensure a certain ease of movement” and “b) The co-existence of gilded greaves and the gold gorytos may signify a common use; that is, the owner of the greaves wore them when he was shooting with bow and arrow in this activity he would be obliged to kneel which would create the need for a different fitting for the greave on the left leg from that of the greave on the right.”

Andronicos offers also a third explanation: “The owner of the greaves had a natural limp and his legs were not of the same length” [1].

Since the leg bones found in the gold larnax showed no differences in length [2], it is difficult to speculate how the left tibia can fit in a shorter greave.

The author (G.S.D.) hypothesized, in a previously published 1986 Greek paper [14], that the problem could be a posterior knee dislocation, resulting from a leg wound, found in old medical literature accounting for leg shortness and consequent lameness.

Regarding the bronze greaves found in the main chamber, appear to belong to the dead king. Greaves were part of an infantryman’s armor; mounted warriors who wear high stout leggings did not wear them. If they belong to Philip they were probably part of his battledress before his leg wound that occurred three years before his assassination and it is reasonable to accept that the lame king fought mounted.

Antikas and Wynn-Antikas re-examined the bones of the male and female of Tomb II using Computerized Tomography (CT) and X-ray Fluorescent Scanning. Their findings failed to show fractures in the male’s leg bones. However, the female bones' examination revealed the following findings: a compression Schatzker type IV fracture undiagnosed in the past but confirmed by CT scans, has disfigured the left tibia plateau, medially. Their conclusion was that the unequal greaves belong to the cremated femalebones found in the larnax of antechamber of Tomb II and the left greave shorter by 2.6 cm and narrower by 3.5 cm. was custommade to fit her leg [3].

There appears to be little doubt that the woman contained in the gold larnax in the sarcophagus of the antechamber was a queen. Andronikos suggested that the woman was Cleopatra, Philip’s seventh wife, without excluding the possibility that she might have been one of the “barbarian” wives (Meda, daughter of a Getic king or the Scythian king’s Atheas daughter) who took her own life or was sacrificed according to barbarian customs [1].

Hammond excludes Cleopatra, since her death "was probably associated with the killing of Attalus, her guardian in 335 BC (Philip II was assassinated in 336 BC) and given the fact the unusual quiver was Scythian, we may suppose that the dead queen was the daughter of king Atheas” [4].

However, according to Hatzopoulos “it’s also known that Cleopatra died (murdered by Olympias?) a few months later. The female buried in the antechamber, the plastering of which, as opposed to that of the main chamber, was properly finished and corresponds to the expected preparations of Cleopatra’s burial, as opposed to the hasty burial of her husband”[5].

Antikas and Wynn-Antikas share Hammond’s version of events that the woman was king Atheas’ daughter. They estimated that her age was 32 ± 2 years, most likely closer to 30, as determined by the symphyseal surface of her left pubis. The pubis fragment was not seen by past researchers, who had estimated her age between 20 and 30 years [2, 15]. They also found 11 Schmorl’s nodes on seven thoracic vertebrae, from T5 to T12, probably due to horse riding having since early youth [3].

Regarding their findings on the thoracic vertebrae, they concluded: “Schmorl’s nodes indicate horse riding; yet some may have resulted from a bad fall that caused her leg fracture. Leg shortening, atrophy, knee disfiguration, pseudoarthrosis and lameness; affirm that the shorter and narrower left greave in the antechamber is hers. Her offensive/defensive weaponry (gold-plated quiver (gorytos), 74 arrowheads, spearheads, linothorax and pectoral, belongs to her and allows the postulate that she was Philip’s II seventh wife/concubine, namely the daughter of King Atheas of Scythia as no other Macedonian king is known to have had relations with a Scythian king at the time.”

The woman’s age estimation by Antikas and Wynn-Antikas based on the symphyseal surface of her pubis bone on the left was criticized. According to Maria Liston, the method used, cannot possibly determine age to that level of precision. Rather it can pinpoint the woman’s age to between 21 and 53 years of age [16].

Leg length inequality can be classified into 3 categories, based on the magnitude of the discrepancy. Mild (for < 3 cm difference), moderate (for >3-6 cm difference) and severe (>6 cm difference) [17].

The Schatzker type IV fracture presented by Antikas and Wynn-Antikas does not show more than a “mild” inequality. Complications of such a fracture may result to lameness, but not shortness of the affected limb [18]. According to the above authors, the greaves belong to the woman in the antechamber and the shorter, narrower left greave affirms that it was custom-made to fit her leg.

The comments of a French archaeologist sited by Andronikos [1] that the greaves “must have belonged to a man because their shape excludes any possibility that they were associated with a woman’s leg” leads to our belief that they can only belong to a woman if she was a long-time trained athlete, not just a rider.

Schmorl’s nodes are commonly found in the human axial spine. In cadaver studies their prevalence has varied from 38% [19] to 58% [20] to 79% [21]. In skeletal remains of horse riders, nodes were found in 7 out of 35 examined specimens [22]. Research has shown strong inherited traits and genetic factors as major determinants in their pathogenesis were demonstrated [23]. Vitamin D deficiency [24], prevalent in Ancient Greece [25], has also been associated with these minor skeletal lesions. The above factors cannot be excluded from the buried woman’s medical history; therefore, the presence of Schmorl’s nodes cannot be considered as an unequivocal indication of the woman being a rider.

Careful observation of the left tibia plateau and fracture published picture, indicates that left leg length inequality cannot be more that 1-2 cm and this would be classified as “mild” one discrepancy. The recorded shortness of the left greave by 3.5 cm or even 2.6 cm (according to Antikas measurement) cannot justify that it was custom-made for the cremated woman’s left tibia. It is our opinion, there is not enough evidence to support the view that the leg fracture of the buried queen, provides indisputable support that the shorter/narrower left gilded greave, belongs to her [3].

The recorded shortness of the left greave is a definite indication of lameness. It could be possible that they were custom-made for Philipp II, to facilitate his lameness. If this is the case we have to accept that the wounded leg was the left and Didymus information regarding the wounded (right) leg, is wrong.

If one considers the greaves do not belong to Philipp II, and since there is no doubt they are parts of a ceremonial armor, the identity of the owner, member of the royal family or at least a noble person and probably a man, entitled to wear such an armor, should be further investigated.

Conclusion

Historical and archaeological assertions are beyond the scope of this paper and the author is not trying to present a new explanation on the identity of the royal woman buried in the antechamber at the Great Tumulus of Aegae, Macedonia, Greece. However, the following points would be made:

a. Hammond was first to identify the woman as a warrior, because of the presence of the gorytus, the arrowheads, the greaves and the pectoral [4], a view shared by other authors as well [3, 26]. It does not appear that there is enough evidence the above armor parts were related and used by the same person.

The gorytos is of Scythian art, whereas the gilded greaves, similar to those found in Tomb III, being part of a ceremonial armor, do not seem to relate in any way with the gorytos.

The gilded pectoral is not made for the court of the Macedonian kings but probably for some Thracianruler [1].

The possibility that the gorytosunique in decoration made for royal use and perhaps the pectoral were war spoils appears strong. As Andronikos points out the gorytos presence in the Tomb II at Aegae is not entirely inexplicable if we recall the frequent clashes between Macedonians and Scythians [1].

b. The length difference of the gilded copper greaves is a strong indication of the lameness of their owner. The greaves are part of a ceremonial armor and apart from Philipp II there is no other member the Macedonian court known to be lame.

c. The shape of the greaves indicates that they belong to a man.

d. The possibility that the greaves are part of the royal armor found in the main chamber cannot be excluded.

e. The fracture of the woman’s left tibia plateau, does not justify the shortness of leg greaves measures; moreover, the presence of Schmorl’s nodes cannot be considered as an unequivocal indication of the woman being a rider.

f. The method of age estimation of the antechamber female by Antikas et al., (32+/-2) has been criticized [16].

Therefore, the possibility ofthe woman found in the antechamber of Tomb IIbeing Philipp’s wife Cleopatra as Andronikos suggested, cannot be excluded.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Drs Antony Okos and John Panayiotides for their comments.

References

- Andronikos M. Vergina: The Royal Tombs. Ekdotike Athinon, Athens. 1984.

- Xirotiris NI, Langenscheidt F. The cremations from the Royal Macedonian tombs of Vergina. Archaiologike Ephemeris. 1981:142-60.

- Antikas TG, Wynn‐Antikas LK. New Finds from the Cremains in Tomb II at Aegae point to Philip II and a Scythian Princess. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 2016 Jul; 26(4):682-92.

- Hammond NG. The royal tombs at Vergina: evolution and identities. Annual of the British School at Athens. 1991 Nov; 86: 69-82.

- Hatzopoulos MB. The Burial of the Dead (at Vergina) or the Unending Controversy on the Identity of the Occupants of Tomb II. Tekmeria. 2008 Jan 1; 9: 91-118.

- Fox RJ, editor. Brill's companion to ancient Macedon: studies in the archaeology and history of Macedon, 650 BC-300 AD. Brill; 2011 Jun 22.

- Bartsiokas A, Arsuaga JL, Santos E, Algaba M, Gómez-Olivencia A. The lameness of King Philip II and Royal Tomb I at Vergina, Macedonia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2015 Aug 11; 112(32):9844-8.

- Delides GS. The Royal Tombs at Vergina Macedonia, Greece, Revisited A Forensic Review. Int J Forensic Sci Pathol. 2016 Apr 15; 4(4):234-9.

- Riginos AS. The wounding of Philip II of Macedon: fact and fabrication. The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 1994 Nov; 114:103-19.

- Harding P. Didymos on Demosthenes. Oxford University Press. Oxford. 2006; 234-238.

- Heckel W. Marsyas of Pella, historian of Macedon. Hermes. 1980 Jan 1; 108(H. 3):444-62.

- Gabriel RA. Philip II of Macedonia: greater than Alexander. Potomac Books, Inc.; 2010 Aug 31.

- Foucart P. Etude sur Didymos d'apres un papyrus de Berlin. Mémoires de l'Institut de France. 1909; 38(1):27-18.

- Delides GS. The differences of the Greaves found in the Royal Tomb at Vergina and the Lameness of Phillip II Αρχαιολογία (Archaiology and Arts). 1986; 18: 63-64.

- Musgrave J, Prag AJ, Neave R, Fox RL, White H. The occupants of Tomb II at Vergina: why Arrhidaios and Eurydice must be excluded. International Journal of Medical Sciences. 2010; 7(6):1-5.

- Pappas St. Burned Bones in Alexander the Great Family Tomb Give Up Few Secrets. Live Science. 2015.

- Gurney B, Mermier C, Robergs R. Effects of leg length discrepancy on gait economy and lower-extremity muscle activity in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001; 83(6): 907-915. PMID: 11407800.

- Zeltser DW, Leopold SS. Classifications in Brief: Schatzker Classification of Tibial Plateau Fractures. Clin OrthopRelat res. 2013; 471(2): 371–374. PMID: 22744206.

- Schmorl G, Junghanns H. The human spine in health and disease. Grune& Stratton . New York. 1971.

- Pfirrmann CW, Resnick D. Schmorl nodes of the thoracic and lumbar spine: radiographic-pathologic study of prevalence, characterization, and correlation with degenerative changes of 1,650 spinal levels in 100 cadavers. Radiology. 2001; 219: 368–374. PMID: 11323459.

- Hilton RC, Ball J, Benn RT. () Vertebral end-plate lesions (Schmorl’s nodes) in the dorsolumbar spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976; 35:127–132. PMID: 942268.

- Anđelinović Š, Anterić I, Škorić E, Bašić Ž. Skeleton changes induced by horse riding on medieval skeletal remains from Croatia. The International Journal of the History of Sport. 2015 Mar 24; 32(5):708-21.

- Williams FMK, Manek NJ, Sambrook PN, Spector TD, Macgregor AJ. Schmorl’s Nodes: Common, Highly Heritable, and Related to Lumbar Disc Disease. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2007; 57: 855–860.

- Kara IS, Calmasur A, Orbak Z, Karavas E, Soyturk M. In 8th International Conference on Children. BioScientifica. 2017 Jul 11; 6.

- Brickley MB, D’Ortenzio L, Kahlon B, Schattmann A, Ribot I, et al. Ancient vitamin D deficiency: long-term trends. Current Anthropology. 2017 Jun 1; 58(3): 420-7.

- Carney E. Commemoration of a royal woman as a warrior: the burial in the antechamber of Tomb II at Vergina. Syllecta Classica. 2017; 27(1):109-49.