Does the Number of Attempts of Endotracheal Intubation Influence the Incidence of Post-Extubation Dysphagia in Patients Undergoing Maxillofacial Surgical Procedures? - A Prospective Analysis

Rajesh P1, Prakyatha Brasanna Shetty2, Vaishali V2*

1 Professor and Head, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, India.

2 Post Graduate, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, India.

*Corresponding Author

Dr.Vaishali. V,

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial surgery, Chettinad Dental College and Research Institute, Kelambakkam, Chennai- 603103, India.

Tel: 8056379290, 8838017051

E-mail: vaish712.venkat@gmail.com

Received: August 16, 2020; Accepted: September 11, 2020; Published: October 22, 2020

Citation:Rajesh P, Prakyatha Brasanna Shetty, Vaishali V. Does the Number of Attempts of Endotracheal Intubation Influence the Incidence of Post-Extubation Dysphagia in Patients Undergoing Maxillofacial Surgical Procedures? - A Prospective Analysis. Int J Dentistry Oral Sci. 2020;7(10):860-863. doi: dx.doi.org/10.19070/2377-8075-20000170

Copyright: Vaishali V©2020. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Aim: To evaluate the incidence and association of post-extubation dysphagia (PED) with varying number of attempts of endotracheal

intubation in patients undergoing maxillofacial surgical procedures.

Settings: One of the unnoticed complications of endotracheal intubation, yet with tragic consequences is post-extubation dysphagia.

In a post maxillofacial surgical patient, this is masked by the extensiveness of the surgery and the immobilization protocols

and hence need to be attended with utmost care.

Materials and Methods: A two-year prospective analysis of patients undergoing maxillofacial surgical procedures for varied

cause was done. Data regarding age, gender, medical history, indication for surgery, pre-anaesthetic evaluation, intraoperative records

related to the number of intubation attempts and any complications associated and a water swallow test to test for PED 24

hours after surgery were recorded and subjected to statistical analysis.

Results: Mean age of the population was 35.1 years and was predominantly male. About 62.5% of them were intubated by fiberoptic

intubation, 35% by naso-endotracheal and 5% by oro-endotracheal intubation.65% of them were intubated more than once

and a maximum of 7 attempts was done to secure the airway. 19 patients had PED and it was significantly associated with the

number of attempts of intubation with p<0.001.

Conclusion: PED is the tip of the iceberg and could indicate a serious underlying complication that could result in fatal complications

if neglected and thus alarms the surgeon to watch out closely and address accordingly.

2.Introduction

3.Materials and Methods

4.Results

5.Discussion

6.Conclusion

7.Refereces

Keywords

Dysphagia; Maxillofacial Surgery; Endotracheal Intubation; Airway.

Introduction

Endotracheal intubation is the choice of securing the airway during

surgical procedures under general anaesthesia. Intubation in

patients indicated for oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures

are quite challenging and different from others. Often difficult intubation

is anticipated with increased extensiveness of the injuries

or pathology and failure of intubation in the first attempt is not

so uncommon. But the post extubation complications associated

as a result has to be attended with care to avoid flare-ups of unnecessary

consequences. One such complication is post extubation

dysphagia especially in maxillofacial surgical patients which in

combination with post-surgical immobilization of the jaw keeps

any serious complications like aspiration pneumonia latent. This

study aims to throw some light on the importance of addressing

the dysphagia in post-surgical patient and to evaluate its incidence

with difficulty in intubation.

Materials and Methods

A prospective analysis of 40 patients who reported to the outpatient

department, and emergency department of our institution

from November 2017 to November 2019 seeking surgical

management of maxillofacial injuries, pathologies and orthognathic

surgeries under general anaesthesia. Ethical clearance was

obtained from the Institutional Human Ethics Committee and

informed consent was obtained from the patients before the surgery.

Patients indicated for Open reduction and internal fixation of various maxillo-mandibular fractures, space infections, surgical

removal of pathologies like cyst enucleation, tumour resection,

cleft repair and removal of temporomandibular joint ankylosis

and those requiring jaw correction surgeries i.e. orthognathic surgeries

were included in the study. Those patients falling under the

categories ASA III and ASA IV, those with surgical airway and

known cases of obstructive and restrictive lung disorders were

excluded from the study. After obtaining informed consent, demographic

details, reason for the indication of surgery, complete

pre-anaesthetic evaluation, intraoperative records of the type of

intubation chosen and the number of attempts for successful intubation,

any other intraoperative complications associated and

incidence of post extubation dysphagia that was recorded with

water swallowing test 24 hours after the surgery. The endotracheal

intubation was performed by the experienced and skilled

anaesthesiologist of our institution. All the data were recorded

and subjected to statistical analysis.

The collected data were analysed with IBM.SPSS statistics software

21.0 Version. Frequency distribution was calculated for categorical.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for numerical data.

Independent t test was used to find the significance and correlation

between variables. In all the above statistical tools the probability

value .05 is considered as significant level.

Results

A total of 40 patients were enrolled in the study. About 82.5%

(n=33) of them were males and 17.5% (n=7) were females. Mean

age of the population was 35.1 years. Figure 1 depicts the frequency

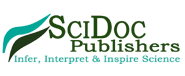

of the type of intubation chosen.

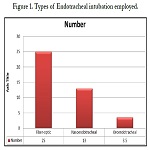

Fiber-optic intubation was the highest used with 62.5% (n= 25), followed by direct nasal intubation in 32.5% (n=13) and finally orotracheal intubation in 5% (n= 2). Table 1 shows the number of attempts used for successful intubation. About 35% (n=14) of the population was intubated successfully in the first attempt, 22.5% (n=9) in their second attempt, 15% (n= 6) in the fourth attempt and 10% (n=4) in the third attempts and rest of them had five attempts and more for successful intubation.

47.5% (n=19) of them were found to have post extubation dysphagia when screened 24 hours after surgery. When the number of intubation attempts and incidence of post-extubation dysphagia was correlated, there existed a positive correlation between both, and it was statistically significant with p<0.001.

Discussion

Securing the airway during maxillofacial procedures is peculiar

from others due to the shared regional anatomy of both. It is

because the maxillofacial injuries have direct impact on the respiratory

tract thereby injuring it as in case of trauma or indirectly

restricting the access due to limited mouth opening or obstructive

nature of the pathology or the tissue injury. This poses a challenge

to the anaesthesiologist to carry out detailed examination of

the upper respiratory tract to opt for the indicated method of securing

the airway. Also, they are not left with the freedom of manipulation

and mobilization of the maxillofacial structures during

examination or intubation due to the extensiveness of the injury

or pathology and due to immobilization protocols to be followed

based on the surgical plan. Prior to the surgical procedure, a thorough evaluation of the patient is mandatory that includes LEMON

assessment - external predictors of the difficult airway that

measures the length of the neck, thyromental distance, atlantoaxial

mobility, Mouth opening, Mallampati classification, and any

obstructed airway seen as stridor and neck mobility [1]. In cases

of maxillofacial trauma, the extent of the fracture, mobile bony

segments, the elevated floor of the mouth, soft tissue edema, and

loose teeth with the risk of aspiration, CSF leak, limited mobility

due to muscle spasm and, in case of any pathology, its extent,

swelling or ulceration, maximum mouth opening, obstructed airway

should be noted and based on the evaluation difficulty of

intubation should be anticipated. Thus the choice of intubation

in maxillofacial surgical procedures is always a team approach and

involves various factors that determine the success of intubation.

Every method of intubation has its indications and contraindications.

However endotracheal intubation either nasal or oral way,

remains the standard way of securing the airway [2]. But limited

mouth opening in maxillofacial surgical patient disables direct

visualization of vocal cords which is a pre-requisite for successful

endotracheal intubation. In such cases, awake fiber-optic intubation

is preferred that enables the anaesthesiologist to visualize the

vocal cords indirectly. The disadvantage that entails this method

is obscuring of vision by salivary secretions and blood but the

failure of intubation is minimal than the other direct techniques

and especially when the mouth opening is compromised. Method

of intubation and its success has important clinical implications.

Complications that results from the endotracheal intubation could

be major or minor [3]. Major complications include granulomas,

laryngeal ulceration or vocal cord injury including paralysis while

minor complications include sore throat, laryngeal edema, stridor

and dysphagia. The severity of complications depends on the

selection of the tube, proper instrumentation and placement of

the tube, number of attempts for successful intubation, duration

of intubation, pre-existing injuries to the airway and extubation

related. One important complication that often goes unnoticed

is the post extubation dysphagia that indicates more serious systemic

issues in a post-operative patient [4].

Post extubation dysphagia is defined as the inability or difficulty

to effectively and safely transfer food and liquid from the mouth

to the stomach after extubation. Clinically it is defined as the inability

to drink 50ml of water within 48 hours of extubation. Leder

et al reported a higher incidence of PED in trauma and critically

ill patients intubated endotracheally for mechanical ventilation

[5]. Multifactorial causation of PED has been described including

mechanical causes, cognitive disturbances and residual effects

of the drugs. Mechanical injury due to improper size of the tube

and prolonged intubation causes mucosal inflammation leading to

loss of architecture, atrophy of the muscles if prolonged, reduced

proprioception and reduced laryngeal circulation. Any dysregulation

in the swallowing reflexes due to neuromuscular disorders or

cognitive impairment due to traumatic brain injury significantly

contributes to PED. Those with neuromuscular disorders, low

Glasgow coma scores, severely injured, old age, prolonged ventilation,

forced supine position, head and neck pathologies, placement

of nasogastric tube adds risk to developing PED. Bordon

et al reported from his study in trauma patients that with every

added day of intubation of the patient, 14% rise in the risk of incidence

of PED and patients who were 55 years of age and above

had 37% increased risk. Macht et al., [6] proposed six mechanisms

to be etiological for PED in post-extubation patients:

1) Direct trauma to the anatomy of the throat (vocal cords, tongue

base, epiglottis, arytenoids by endotracheal or tracheostomy tubes

2) Muscular weakness due to nerve and muscle damage (disuse

atrophy; critical illness neuropathy and myopathy

3) Loss of normal sensation in the oropharynx and larynx

4) Impaired sensorium generally (delirium, sedation)

5) Gastroesophageal reflux

6) Out-of-sync breathing and swallowing in people with tachypnea

before and/or after extubation.

Undiagnosed dysphagia in post-extubation patients leads to bronchoaspiration

and related complications like pneumonia, malnutrition,

increased hospital stay and thereby interferes the recovery

period of the patient. Sassi et al reported that 50% of the patients

with difficult or prolonged intubation that presented with postextubation

dysphagia developed broncho-aspiration7. Such scenario

gets worse in a maxillofacial patient due to the overt influence

of other factors like static immobilized jaw, pain and swelling

with alternative route of nutrition that narrows the focus of the

patient and the surgeons during the first few days after surgery.

Meanwhile in rare occasions, if the respiratory and pharyngeal

complications are not treated results in catastrophic complications

leading to morbidities and mortalitites.

A number of methods are in use to diagnose PED [7]. Commonly

used method is the bedside evaluation (BSE) by a speech

pathologist. It is a multifaceted test comprising of an interview,

clinical assessment of respiratory tract and functional changes if

any. Another most often employed screening test for dysphagia is

the water swallow test [8]. When the severity of the condition has

to be graded, various other instrumental tests are preferred. Video

fluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS), Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation

of swallowing, Ultrasonography, pH manometry and scintigraphy.

Of these VFSS and FEES are considered to be the gold

standard for diagnosis of PED as they portray a real time image

of various deglutition stages which aids in the accurate diagnosis

and prompt management of the condition [3]. In maxillofacial

surgical patients it is mandatory to check for the incidence of

PED post-surgically. In many instances PED is either unnoticed

due to the extensiveness of the surgery or masked by the jaw

immobilization protocols. The same reason calls for alternative

methods of nutrition to not interfere in the healing of the surgical

wound. By the time the patient reverts to oral intake, any minor

injuries to the pharynx would have healed and thus passes unseen.

This study intended to uncover the latent threat of the PED, even

if rare, and highlight the importance of thorough examination of

the patient during the post surgical period to watch out for any

signs and symptoms of PED though could be indicating an ongoing

aspiration pneumonia or related complications.

In our study, the mean age group of the population was 35.1 years

and the gender was predominantly male. This relieves the influence

of age on the incidence of dysphagia thereby eliminating

the confounding bias. Fiber-optic intubation was the frequently

chosen method of intubation (62.5%) followed by direct nasoendotracheal

intubation (35%) and finally by the oro-endotracheal

intubation. This differs from the results of the Sarasvat et al., and

Rashiuddin et al., where direct nasal intubation was the preferred

choice of intubation [9]. But this could be because those studies

involved only maxillofacial trauma while in our study patients

undergoing all types of maxillofacial surgical procedures were involved. Also the demographics, extensiveness of the etiology,

anticipated difficulty in airway and the anaesthesiologists’ preference

has a major role in the choice of airway. About 65% of

the patients were not intubated successfully in the first attempt.

22% had to be intubated twice, 15% four times and 10% three

times and the rest multiple times for a successful intubation. This

could be attributed again to the complexity of the injuries and

their obscurity to the evaluation. Significant proportion of the lot

developed PED (47.5%) and it had a strong positive correlation

with the number of failed attempts of intubation. Thus difficult

intubation could indicate potential complication of PED in the

post-surgical period.

Thus it is expected of every maxillofacial surgeon to express a

high index of suspicion during their evaluation for the symptoms

of PED to avoid unlikely complications. Knowledge of the attributes

of difficult airway, skills of managing the same, accurate

recognition of a failed airway is important while securing the airway

[10].

Conclusion

Post extubation dysphagia is not uncommon even in patients

without pre-existing pathologic states. Owing to the life threatening

consequences that could occur if PED is neglected, every

maxillofacial surgeon to monitor the patient closely. The risk of

dysphagia escalates with increased attempts of endotracheal intubation

and it should alarm the surgeon to anticipate PED and

watch out for the same to effectively manage the condition.

References

- Raval CB, Rashiduddin M. Airway management in patients with maxillofacial trauma - A retrospective study of 177 cases. Saudi J Anaesth. 2011; 5(1): 9-14. PMID: 21655009.

- Barak M, Bahouth H, Leiser Y, Abu El-Naaj I. Airway Management of the Patient with Maxillofacial Trauma: Review of the Literature and Suggested Clinical Approach. Biomed Res Int. 2015; 2015: 724032. PMID: 26161411.

- Tay JYY, Tan WKS, Chen FG, Koh KF, Ho V. Postoperative sore throat after routine oral surgery: influence of the presence of a pharyngeal pack. British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 2002; 40(1): 60–63.

- Rassameehiran S, Klomjit S, Mankongpaisarnrung C, Rakvit A. Postextubation Dysphagia. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2015 Jan; 28(1):18-20. PMID: 25552788.

- Leder SB, Cohn SM, Moller BA. Fiberoptic endoscopic documentation of the high incidence of aspiration following extubation in critically ill trauma patients. Dysphagia. 1998; 13(4): 208–212. PMID: 9716751.

- Macht M, Wimbish T, Clark BJ, Benson AB, Burnham EL, Williams A, et al. Postextubation dysphagia is persistent and associated with poor outcomes in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care. 2011; 15(5): R231. PMID: 21958475.

- Medeiros Gisele Chagas de, Sassi Fernanda Chiarion, Mangilli Laura Davison, Zilberstein Bruno, Andrade Claudia Regina Furquim de. Clinical dysphagia risk predictors after prolonged orotracheal intubation. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2014; 69( 1 ): 8-14. PMID: 24473554.

- Tsai MH, Ku SC, Wang TG, Hsiao TY, Lee JJ, Chan DC, et al. Swallowing dysfunction following endotracheal intubation: Age matters. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016; 95(24): e3871. PMID: 27310972.

- Saraswat V. Airway management in Maxillofacial trauma: A Restrospective Review of 127 cases. Indian J Anaesth. 2008; 52: 311-6.

- Skoretz SA, Flowers HL, Martino R. The Incidence of Dysphagia Following Endotracheal Intubation. Chest. 2010; 137(3): 665–673. PMID: 20202948.